Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes

June 16, 2013 to September 8, 2013

Kimbell Museum

"The Wari civilization formed in the wake of a late-sixth-century drought that ravaged the central Andean region of what is today Peru and parts of adjacent countries. It was a new cultural experiment that, over the next four centuries, produced a society of such unprecedented complexity that many today regard it as South America’s first empire. As predecessors of the Inca Empire, which fell to Spanish forces after 1532, the Wari had no previous examples of expansionist states to draw upon and thus represent a major development in Andean civilization.

Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes, arriving at the Kimbell in June 2013, explores the Wari accomplishment through some 140 artworks in all major media in which they worked—polychrome ceramics, ornaments made of precious metals or colorful mosaics, sculptured wood and stone objects, and textiles of striking complexity. Together, these works paint a picture of the Wari state and offer insights into their expansion strategies.

Unlike their Maya contemporaries, the Wari never developed a written language. Thus, modern opinion about their achievement is based exclusively on their artwork and other material remains. In the absence of writing, the artworks that circulated throughout Wari society acted as vehicles of communication, recording and preserving the way in which the Wari regarded themselves, nature, and the divine realm. Many of the Wari’s greatest artistic accomplishments are realized in small, portable items—such as a Bag with Human Head—which could be transported across the Andean region, spreading the Wari culture to diverse and distant communities. It is through these images that we are able to gain access into the values and beliefs that shaped Wari society and contributed to its imperial expansion.

The exhibition is organized in four thematic sections. The Gift of Food and Drink presents vessels reconstructed from a three-ton buried deposit of deliberately shattered ceramics that may represent an offering of wares used in official feasts. Such feasts were lavish affairs with food and chicha (native corn beer) and apparently were a major element of Wari statecraft. They allowed Wari hosts to build prestige, assert authority, and indebt guests, since, then as now, gifts of any kind are rarely free. Wari feasts may have capitalized on the Andean belief that the world exists due to the interaction of two forces harmonized through the mutual dependence that reciprocity creates.

The Wari Realm demonstrates the spread of Wari imagery—most importantly, a staff bearing deity that was the focus of Wari state religion—to many areas of the Andes. This frontally posed supernatural being—seen, for example, on the Urn with Staff Deities—is probably a nature deity, perhaps the sun or thunder. It carries staffs of authority and is sometimes flanked by profile attendants in a formal expression of hierarchy that may have paralleled the Wari earthly political structure. Though the role of religion in the Wari’s expansion is not well understood, images such as this make it seem likely that religion and politics were part of a single process. Indeed, the art suggests that Wari lords drew their authority to some degree from affiliation with the divine and that they may have owed their success in part to the belief that they could mediate human and cosmic matters, thus shaping the lives of women and men.

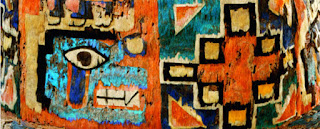

The Art of Regalia examines the regalia worn by Wari lords and the spread of these objects to different places in the Andes, many perhaps as diplomatic gifts that fostered alliances or as imports treasured for their prestige. Among them are textiles—a crucial Andean art form—including elaborate tapestry-woven tunics, vibrantly colored tie-dyed garments, and cloth lavishly covered with exotic feathers. Remarkably, many of these Wari textiles have immediate contemporary appeal; the brightly hued tunics, worn as emblems of status, exhibit a penchant for hard-edged geometric shapes and intricate color patterning across a flat surface. Moreover, the sophisticated designs of the tapestry-woven tunics, the garments of elites and rulers, demonstrate an aptitude for experimenting with the form that is on par with twentieth-century artists. Also featured in this section are personal ornaments made of precious mosaic or noble metals.

Offerings and Ancestors considers offerings that the Wari made in varied contexts. One of the most common was the tombs of the honored dead, where many of the exhibition’s objects likely were found. The characteristics of highland tombs suggest that Wari elites venerated important ancestors, who probably endowed descendants with legitimacy and spiritual protection. The Wari also buried fine objects in offerings unassociated with human remains; these likely had varied votive or dedicatory purposes that are still under study. The most elaborate of such offerings included human figurines or well-decorated ceramics that were deliberately shattered in rites that must have impressed all who witnessed them.

Wari: Lords of the Ancient Andes is only the second exhibition in the world to be devoted to the arts of the Wari Empire, and the first of its kind in North America. Bringing together objects from public and private collections all over the world, including several objects that have never been seen outside the countries in which they now reside, this exhibition offers a unique opportunity to experience an extraordinary civilization in great depth and detail.

This exhibition is organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art. It has been made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities: Exploring the human endeavor. It is supported in part by the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities." Kimbell Museum

No comments:

Post a Comment