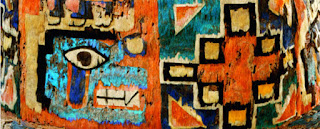

I recently saw this announcement of an African exhibition of "three-dimensional traditional art from the early to mid 20th century". The Georgia Musem of Art is the official state museum of Georgia and is located in Athens, Georgia. Most museum goers are not going to pick up on exactly what this statement means, but it is providing some very definitive information about the works of art in this exhibition. It is categorically stating that exhibition consists of art made for appropriate ceremonial use by and for the appropriate ethnic group that would normally be expected to make and use such objects. The collection is owned by Don Kole, Chairman Emeritus of the Georgia Historical Society. I don't know Mr. Kole although I recall a request for an appraisal of African art many years ago from Savannah. I have no recollection if this is the same collector. I do know that knowledgeable colleagues have told Mr. Kole that a substantial portion of his collection is not traditional amd was made for sale. At this point I have no idea if these are the same pieces in this museum exhibition. From the photos I have seen of a Pende mask, a Yoruba beaded robe, and a Kongo nail fetish, there are certainly stylistic elements in these objects that raise red flags for me. If Mr. Kole wants to send me a disk, I would be happy to comment on the exhibition. Regardless of what Mr. Kole does, the museum has a responsibility to their supporters and visitors to ensure that any exhibition they mount is represented correctly.

ATHENS, GA.- "The Georgia Museum of Art at

the University of Georgia presents the exhibition “From Savanna to Savannah:

African Art from the Collection of Don Kole” from Jan. 19 to April 14, 2013.

Featuring more than 40 works of three-dimensional traditional art from the early

to mid-20th century, the exhibition includes sacred, meaningful objects created

by numerous peoples in sub-Saharan Africa. Works of art in various media—wood,

bronze, terracotta, sandstone and cloth—from regions as diverse as Cameroon,

Guinea, Tanzania and the Democratic Republic of Congo present examples from the

visual and material culture of Africa that demonstrate cultural concepts and

religious beliefs.

Chief curator and curator of American art Paul Manoguerra organized the exhibition from the collection of Don Kole, a Savannah-based real estate investor, with the assistance of William Darrell Moseley, a Tennessee-based expert in African art. Kole and his wife, Kaye, have long been passionate about African art and have made numerous trips to the continent to build their collection and educate themselves about traditional arts.

Manoguerra said, “These objects on display from the Kole Collection present the passion and enthusiasm of a Georgia collector for African art. The Georgia Museum of Art is proud to show these works of art from the Kole Collection and to display this sampling of the aesthetics of African art.”

Objects on view include furniture, masks, fertility dolls, pottery, weaponry, musical instruments and clothing, many of which bear elaborate decoration in the form of carving, paint or beading. The influence of African art on modern art is well documented, but Manoguerra said he believes these works can stand on their own aesthetically without being tied to the Western art historical canon.

This exhibition is part of an ongoing initiative by the museum to deal with African and African American themes, sparked in part by Larry and Brenda Thompson’s gift in early 2012 of a large collection of works by African American artists. Much of that gift is currently on tour in the exhibition “Tradition Redefined: The Larry and Brenda Thompson Collection of African American Art,” which will open at the Knoxville Museum of Art in April 2013. GMOA has a history of displaying African art that dates as far back as the 1970s, although it has been some time since its last exhibition on the subject." artdaily.org

Chief curator and curator of American art Paul Manoguerra organized the exhibition from the collection of Don Kole, a Savannah-based real estate investor, with the assistance of William Darrell Moseley, a Tennessee-based expert in African art. Kole and his wife, Kaye, have long been passionate about African art and have made numerous trips to the continent to build their collection and educate themselves about traditional arts.

Manoguerra said, “These objects on display from the Kole Collection present the passion and enthusiasm of a Georgia collector for African art. The Georgia Museum of Art is proud to show these works of art from the Kole Collection and to display this sampling of the aesthetics of African art.”

Objects on view include furniture, masks, fertility dolls, pottery, weaponry, musical instruments and clothing, many of which bear elaborate decoration in the form of carving, paint or beading. The influence of African art on modern art is well documented, but Manoguerra said he believes these works can stand on their own aesthetically without being tied to the Western art historical canon.

This exhibition is part of an ongoing initiative by the museum to deal with African and African American themes, sparked in part by Larry and Brenda Thompson’s gift in early 2012 of a large collection of works by African American artists. Much of that gift is currently on tour in the exhibition “Tradition Redefined: The Larry and Brenda Thompson Collection of African American Art,” which will open at the Knoxville Museum of Art in April 2013. GMOA has a history of displaying African art that dates as far back as the 1970s, although it has been some time since its last exhibition on the subject." artdaily.org

Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller. © abm – Barbier-Mueller Archives.

Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller. © abm – Barbier-Mueller Archives.